Understanding the SynchronizationContext in .NET with C#

Updated on 2020-07-28

Take control of which thread your code gets executed on, and how it does

Introduction

Here, I intend to shed some light on another dark corner of the .NET framework - synchronization contexts. I will take you through understanding why they exist, what they do, and how they work. In the end, we are even going to implement our own. This article assumes at least a passing familiarity with multithreading. It doesn't require that you have written much if any multithreaded code before, as long as you understand the core principles and caveats of it. I'll be covering a little bit of it anyway.

Note: This article's source code includes the rest of my Tasks framework as it exists so far. The relevant projects are SyncContextDemo, and Tasks. Under Tasks, you'll find MessagingSynchronizationContext.cs, which uses MessageQueue.cs which is auxiliary.

Update: It may not have impacted your existing code, but there is a potential problem with the first revision wherein the SemaphoreSlim and the ConcurrentQueue

Conceptualizing this Mess

What is a Synchronization Context?

First let's talk about the problem it solves. With multithreaded code, you can't simply read and write values across threads with impunity, which also implies you can't just call methods and properties across threads either because you might cause a race condition, which is one of the worst things to have to debug in programming. Writing multithreaded code is complicated, easy to get wrong, and hard to debug. There's got to be an easier way!

I'd like to entertain a funny idea: consider that there are "boundaries" between threads - invisible walls you have to get through. Between those walls is where your (member) data lives. Don't cross those boundaries without preparation. If you've written multithreaded code, this should be easy to grasp if not utterly familiar.

How do we cross those boundaries? It depends. There are many ways to do so, a couple of primary ones being somewhat crude synchronization primitives (like mutexes and semaphores), and much more advanced message passing (which actually builds on synchronization primitives.)

The question is, can we abstract something that is flexible that allows us to communicate across thread boundaries regardless of the underlying implementation, and present a facade to the developer that makes it easy to use?

The answer is essentially yes, and that's what Microsoft did with the SynchronizationContext. This is basically a contract class, because you derive from it in order to make it do anything. The default implementation just hops over the wall without doing any synchronization.

However, you're sometimes not dealing with the default synchronization context. WinForms has its own that it uses to help you for example, safely run BackgroundWorker tasks and report back to the UI even though the reporting starts off in separate thread than the UI thread. Remember you can't just cross a thread boundary like that.

The SynchronizationContext and its derivatives work like a message queue, or at least that's the facade they present to the developer. With it, you can execute delegates in one of two ways on the target thread - the one where our message loop "lives". We'll get to the message loop in a bit. The first way to dispatch a delegate to a target thread is Post() and it's asynchronous, but it doesn't let you know when it finished. The second way is Send() which is synchronous and blocks the sender until the recipient completes execution of the delegate. That's not great, but it's what we have. Due to the nature of message queues, bidirectional communication isn't possible - they're one way so you'd need two. That's why Post() doesn't notify you.

The other thing about a synchronization context is each thread can be associated with one. This is sometimes but not always the same thread with the message loop that looks for incoming messages. Delegates can be dispatched to the thread running a message loop so that the thread may execute them. We'll cover what it looks like further down.

Why Abstract it at All?

This is a good question. The answer is that you can extend it and some of the framework can consume it. The await mechanism inserts calls to it into the code for your async routine in order to make sure the code before await and the code after await execute in the same context (on the same thread). Other times, the framework will provide its own, like the one WinForms implements, which keeps the UI thread safe when for example, a BackgroundWorker (which consumes it) communicates with it.

Coding this Mess

How Do We Use It?

You can get the current synchronization context for a thread by retrieving SynchronizationContext.Current. You can set it by calling SetSynchronizationContext().

Once you have it you can call Post() to fire and forget a delegate on the SynchronizationContext's associated message loop thread, or you can call Send() to block until the foreign execution is complete.

If you create a new thread, you can set its synchronization context to the one that's driven by your UI thread - the thread with your Forms on it, where you called Application.Run() because that's where the WinForms synchronization context runs. So you do like:

// in a Winforms app UI thread somewhere:

var sctx = SynchronizationContext.Current;

var thread = new Thread(() => {

// now await and other things can dispatch messages to

// to sctx which here in WinForms will be the UI's

// SynchronizationContext:

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(sctx);

// ... do work including sctx.Post() and/or sctx.Send()

});

thread.Start();You don't really need to set the thread's synchronization context in the case where we used it above, because we have access to sctx directly so we didn't have to query SynchronizationContext.Current but other things, like await rely on it, so you really should set it.

Once you have one, either by retrieving the Current property, or by hoisting like we did above, we can call Post() and Send().

Your message, which is typically transmitted from another thread, is then dispatched on the receiving context's associated message loop thread. The transmitting of messages looks like this:

// executes on the target thread, not this thread:

sctx.Post((object state) => { MessageBox.Show(string.Format("Hello from thread {0} (via Post)",

Thread.CurrentThread.ManagedThreadId)); }, null);The anonymous method executes on the target thread, in this case, the UI thread, where calls to MessageBox.Show() are safe.

Send() works exactly the same way except it blocks until the target delegate has completed executing.

We can use these to basically shift code to other threads as long as those threads have message loop and a synchronization context.

How Does It Work?

It's not magic, it's just messaging, I promise. First to understand it, let's take a look at a message loop for a particular implementation of a SynchronizationContext I built:

Message msg;

do

{

// blocks until a message comes in:

msg = _messageQueue.Receive();

// execute the code on this thread

msg.Callback?.Invoke(msg.State);

// let Send() know we're done:

if (null != msg.FinishedEvent)

msg.FinishedEvent.Set();

// exit on the quit message

} while (null != msg.Callback);I don't especially like the name Callback but I used it because that's what Microsoft calls it in their default implementation and the delegate Send() and Post() take. What it is is the delegate (usually to an anonymous method) containing the code to execute, like we did with Post() and Send() before. If it's null, that signifies to stop the message loop but this detail is specific to my implementation. Finally, we simply call the delegate we received in the message, since now we're on the target thread.

Now let's look at the demo, which is illustrative, if contrived:

// determine if we are using a synchronization context other than the default

// if it's null, we're using the default, which executes code on the same thread

// that Send() or Post() sent it on.

Console.WriteLine("Current thread id is {0}", Thread.CurrentThread.ManagedThreadId);

Console.WriteLine("Synchronization context is {0}set",

SynchronizationContext.Current == null?"not ":"");

// create a new custom synchronization context

var sc = new MessagingSynchronizationContext();

Console.WriteLine("Setting context to MessageQueueSynchronizationContext");

// now start our message loop, and an auxiliary thread

Console.WriteLine("Starting message loop for thread {0}",

Thread.CurrentThread.ManagedThreadId);

var thread = new Thread(() => {

// always set the synchronization context if you'll be using

// a non-default one on the thread

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(sc);

// don't use the synchronization context - posts from this thread:

Console.WriteLine("Hello from thread {0}", Thread.CurrentThread.ManagedThreadId);

// use the synchronization context - posts from Main()'s thread:

sc.Post((object state) => { Console.WriteLine("Hello from thread {0} (via Post)",

Thread.CurrentThread.ManagedThreadId); }, null);

});

// start the auxiliary thread

thread.Start();

var task = Task.Run(async () =>

{

// set the synchronization context

// uncomment this to see what happens!

// SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(sc);

Thread.Sleep(50);

Console.WriteLine("Awaiting task");

await Task.Delay(50);

// this will wake up on main thread or not

// depending on the synchronization context

Console.WriteLine("Hello from thread {0} (via await)",

Thread.CurrentThread.ManagedThreadId);

});

// start the message loop:

sc.Start(); // blocks

// doesn't matter but shuts up the compiler:

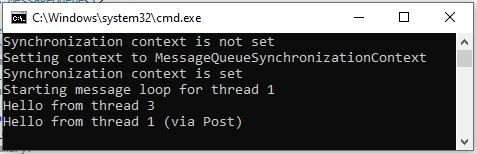

await task;It should output something like this:

Current thread id is 1

Synchronization context is not set

Setting context to MessageQueueSynchronizationContext

Starting message loop for thread 1

Hello from thread 3

Hello from thread 1 (via Post)

Awaiting task

Hello from thread 4 (via await)Now try uncommenting this line (where it says "see what happens!"):

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(sc);Now run the program. This time it said thread 1 (or whatever your current thread id said). You'll note that the await this time didn't cause the code to execute on a new thread. What's this sorcery? awaits use the current synchronization context to execute code that comes after the await:

var sctx = SynchronizationContext.Current??new SynchronizationContext();

sctx.Post(()=>{ /* next portion of code */ },null);I'll explain more later.

Note that SynchronizationContext does not have a Start() method on it. How the message loop a synchronization context uses is implemented is an opaque detail we're not supposed to consider. However, in our custom implementation, we need something to serve as our message loop, and I essentially just provided a boilerplate one behind that method to keep things simple.

If you don't quite understand how it works yet, let me go over it again. Somewhere, there's a message loop. Where it is in your code or the bowels of the framework is an implementation detail. The point is that whatever thread it runs, the message loop on is where the code will finally be executed. You call Send() and Post() from other threads with delegates "containing" your code to be "transported" and executed on that target thread. This allows for easy cross thread communication.

How Do You Make Your Own?

Sometimes, like when you're in a console app or Windows service, you will not have a good SynchronizationContext to use. The problem is there's no message loop. If you want one, you have to make one, and that's what this is for. It should be sufficient for custom threading scenarios where you need code executed on a thread of your choosing. We'll explore it here. First, we have a nested struct declaration and an important member field:

private struct Message

{

public readonly SendOrPostCallback Callback;

public readonly object State;

public readonly ManualResetEventSlim FinishedEvent;

public Message(SendOrPostCallback callback,

object state, ManualResetEventSlim finishedEvent)

{

Callback = callback;

State = state;

FinishedEvent = finishedEvent;

}

public Message(SendOrPostCallback callback, object state) : this(callback, state, null)

{

}

}

MessageQueue<Message> _messageQueue = new MessageQueue<Message>();The message contains the "callback" I mentioned earlier, a field for optional user state which you passed to Send() or Post() and finally a ManualResetEventSlim which I'll explain as we get further along. It is used for signalling to Send() that we've processed the message so that Send() is able to block until it's received. This type declares all the information we need to execute a delegate on the message loop thread.

Next, we have something called a MessageQueue that holds Message struct instances as declared above. This class provides a thread safe way to communicate by posting and receiving Messages. It does most of the heavy lifting, but we'll explore that as well eventually.

The above is specific to our implementation of a SynchronizationContext. You may very well have your own way of communicating across threads, and you can implement whatever you like as long as it fulfills the necessary contract provided by SynchronizationContext.

Here are the Send() and Post() implementations for our custom synchronization context:

/// <summary>

/// Sends a message and does not wait

/// </summary>

/// <param name="callback">The delegate to execute</param>

/// <param name="state">The state associated with the message</param>

public override void Post(SendOrPostCallback callback, object state)

{

_messageQueue.Post(new Message(callback, state));

}

/// <summary>

/// Sends a message and waits for completion

/// </summary>

/// <param name="callback">The delegate to execute</param>

/// <param name="state">The state associated with the message</param>

public override void Send(SendOrPostCallback callback, object state)

{

var ev = new ManualResetEventSlim(false);

try

{

_messageQueue.Post(new Message(callback, state, ev));

ev.Wait();

}

finally

{

ev.Dispose();

}

}You can see Post() is straightforward. Send() is slightly more complicated because we must get notified when it finally completes, which is what our ManualResetEventSlim from earlier was before. Here we create it, post it with the Message, and then wait on it. In our message loop, it gets Set() signalling we can continue. Finally, we Dispose() of the event. It might be more efficient to recycle these events but doing so is significantly more complicated and I'm not sure how much performance would be gained, if any.

Note we can pass a State with the Message. It gets sent to the Callback for processing, and its value is arbitrarily defined by the consumer.

Now let's look at our message loop in Start() again, hopefully it will be a little clearer this time:

Message msg;

do

{

// blocks until a message comes in:

msg = _messageQueue.Receive();

// execute the code on this thread

msg.Callback?.Invoke(msg.State);

// let Send() know we're done:

if (null != msg.FinishedEvent)

msg.FinishedEvent.Set();

// exit on the quit message

} while (null != msg.Callback);While Stop() looks like this:

var ev = new ManualResetEventSlim(false);

try

{

// post the quit message

_messageQueue.Post(new Message(null, null, ev));

ev.Wait();

}

finally {

ev.Dispose();

}Note how we're waiting for the message to complete. The reason this doesn't use Send(), but does the same thing is I've been considering adding a check for a null Callback and throwing in Send() if it finds one. This code ensures that the behavior here won't break if I add that check.

What About the MessageQueue Class?

The MessageQueue provides the core functionality to post and receive messages between threads. It uses ConcurrentQueue

T result;

_sync.Wait();

if (!_queue.TryDequeue(out result))

throw new InvalidOperationException("The queue is empty");

return result;Meanwhile, Post() (there is no Send() equivalent) simply works like this:

_queue.Enqueue(message);

_sync.Release(1);That's the meat of it. There are several variants that do awaitable operations and/or take CancellationTokens but they all do the same thing as the above effectively.

Await and SynchronizationContext

The await language feature typically generates code for you that uses the thread's synchronization context. Every time an await is found, a new state for the state machine it builds out of your method is created so that it can suspend the execution of the method. The method becomes restartable, and works very similarly to how C# iterators and yield work in terms of how it modifies and morphs your code. The problem is that your method is often "restarted" after the await on a different thread, due to being hooked into device I/O callbacks or being "awoken"/unsuspended by another OS thread. What you need is seamless transition of your code back to the original thread and that's exactly what await provides. It uses the thread's current SynchronizationContext to run the restarted method on the thread the routine was originally called from, using either Post() or Send(). This is why it's important to set the SynchronizationContext especially if you're using async/await and you need a custom one, like the one above.

However, if you configure the Task by using ConfigureAwait(false) it will override the typical behavior, and the current synchronization context will not be used, making the behavior the same as it would be when no synchronization context is set.

History

- 26th July, 2020 - Initial submission

- 28th July, 2020 - Update 1 (bugfix)